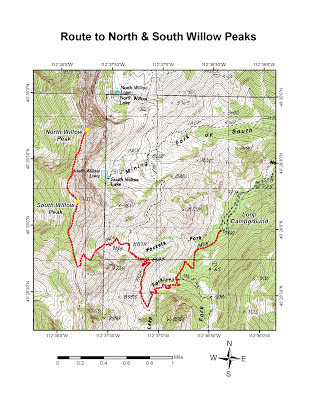

There are two main routes to access South Willow Lake. A more direct, yet steeper route begins at the Medina Flat Trailhead of South Willow Canyon, which is just above the Boy Scout Campground to the north of the main road. This route crosses a ridge into the Mining Fork of South Willow Canyon – where the drainage is basically followed up to the lake. The route that I took however begins at the Loop Campground in South Willow Canyon along with other hikes in this mountain range. To reach the trailhead where I started, follow the same directions listed in the previous post on North and South Willow Peaks.

|

| View of the approach to South Willow Lake below the unnamed cirque |

The trail begins near the restrooms at the top of the Loop Campground and enters the Deseret Peak Wilderness Area several hundred feet beyond the information sign. Once the trail crosses the streambed and splits at approximately 0.7 miles, take the right fork towards the Pockets Fork of South Willow Canyon. Deseret Peak comes into view when the Dry Lake Fork streambed is crossed after another 0.6 miles, and the view basically remains unobstructed until the crest of the ridge is reached before Pockets Fork. At approximately 1.4 miles beyond the first trail split, the trail splits again in the Pockets Fork drainage – where you will continue straight (northward) towards South Willow Lake. From this point the trail terraces the mountainside around a second ridge and then drops into the Mining Fork drainage. After crossing the Mining Fork streambed, the trail splits a third time where the left fork is taken (westward) for the final half-mile climb to the lake. This stretch is the steepest part of the hike, which ascends about 460 feet to reach the 9,140-foot elevation of South Willow Lake. Distance from the trailhead to South Willow Lake is approximately 3.6 miles one-way with an elevation gain of about 2,000 feet (taking into account a 460-foot gain after a 260-foot loss).

|

| South Willow Lake as viewed near the north shoreline |

|

| South Willow Lake as viewed near the southeast extension |